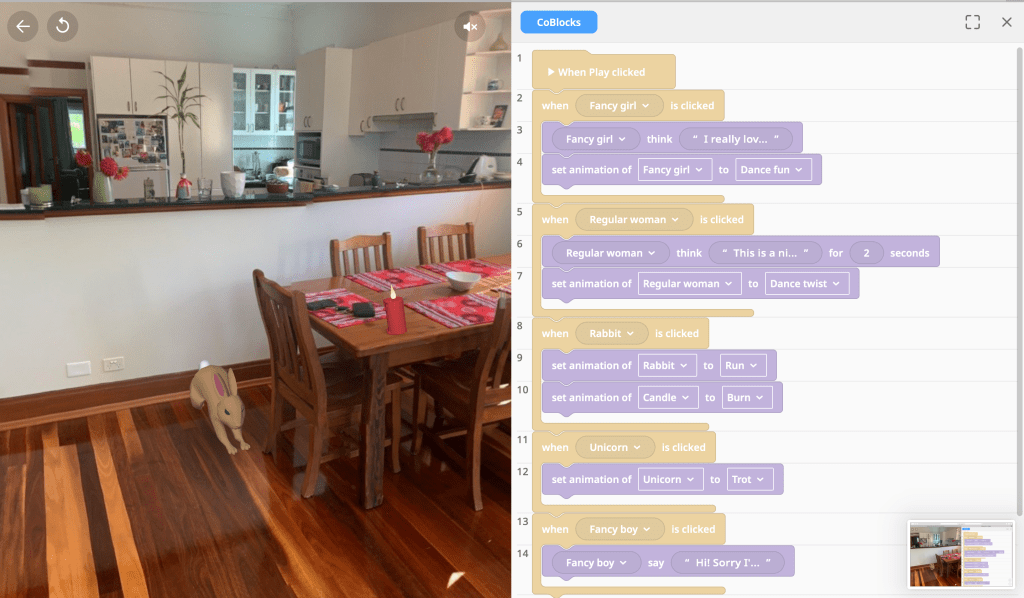

Augmented Reality (AR) is an integration of a virtual world into the real world. It provides additional details to a real-world place, such as an overlay of audio, graphics, and other virtual elements (Green, Green & Brown, 2017). This blog will explore the power of AR within the classroom, including the promotion of creativity and also assess the extent to which the application ‘Quiver’ utilises these capabilities. In the classroom, AR has been shown to increase intrinsic motivation as it develops student’s interests, resulting in students consolidating their learning (Billinghurst & Duenser, 2012).

Case study

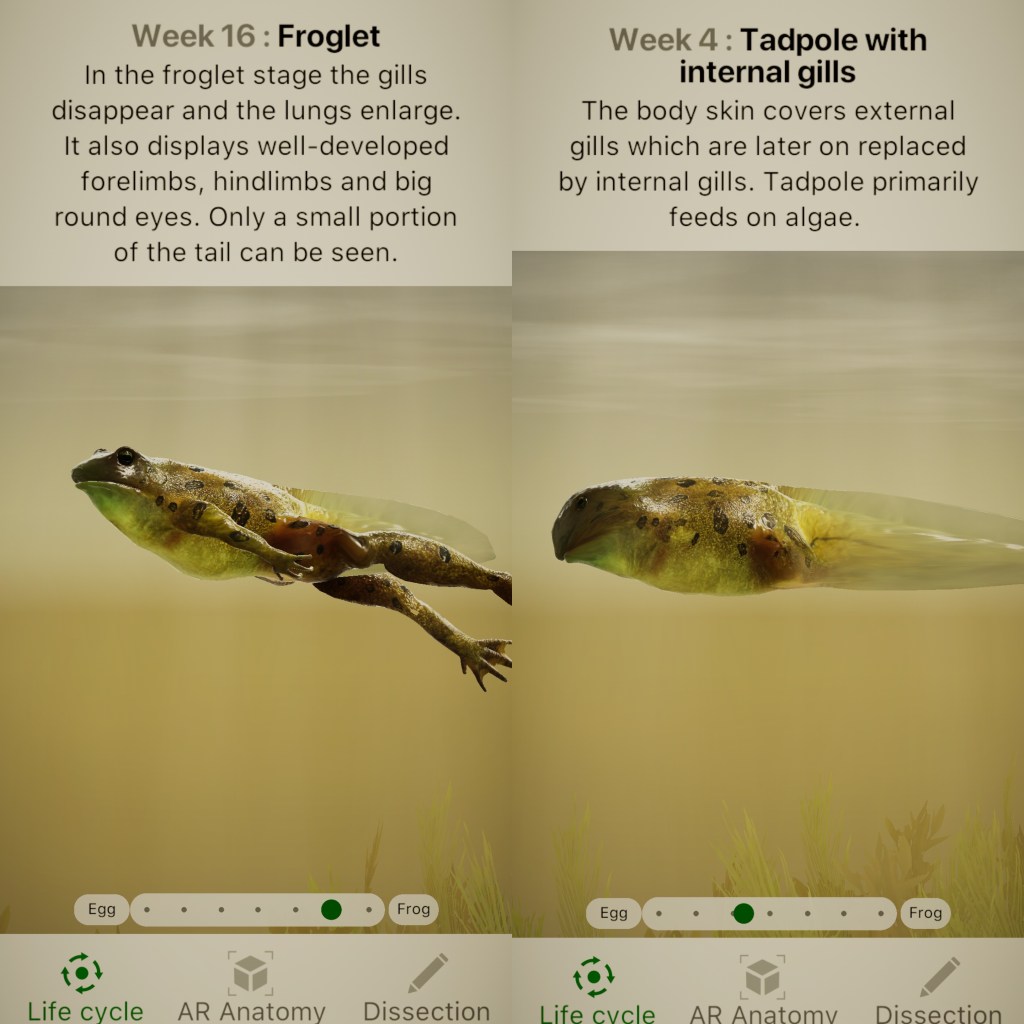

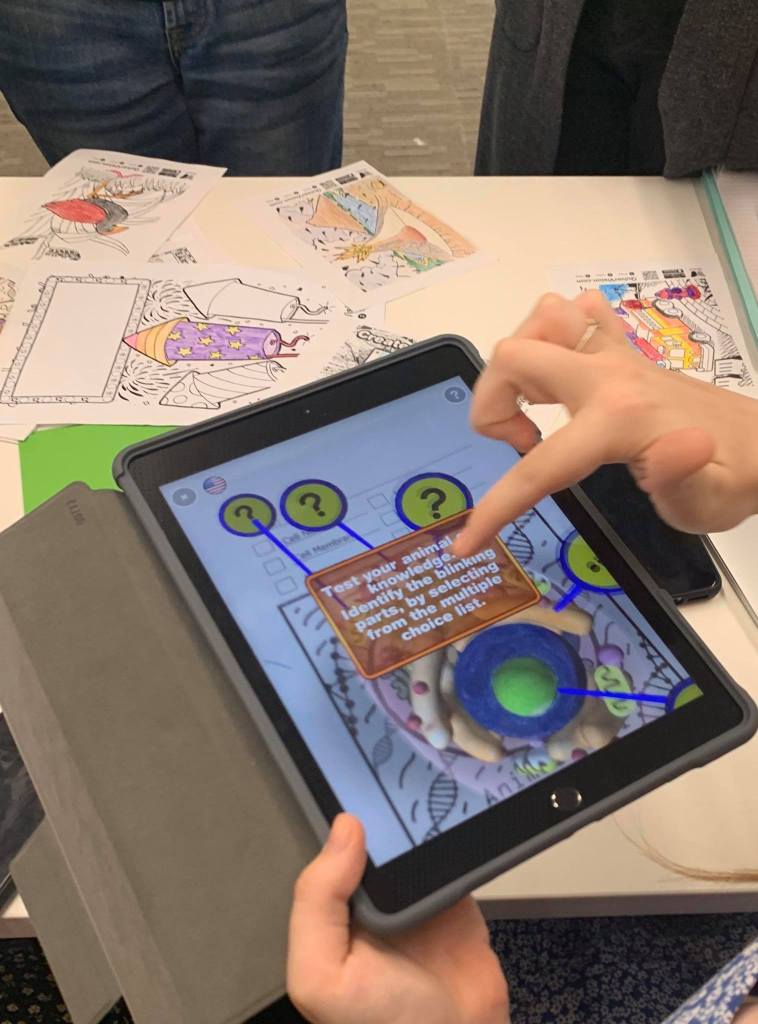

‘Quiver’ is an example of Augmented reality that can be used in the classroom. This app allows students to colour in set pictures which they can scan, view in 360 and edit on their iPads. Some sheets, when scanned include labels and a quiz, however others only provide 3D views of an otherwise 2D colouring.

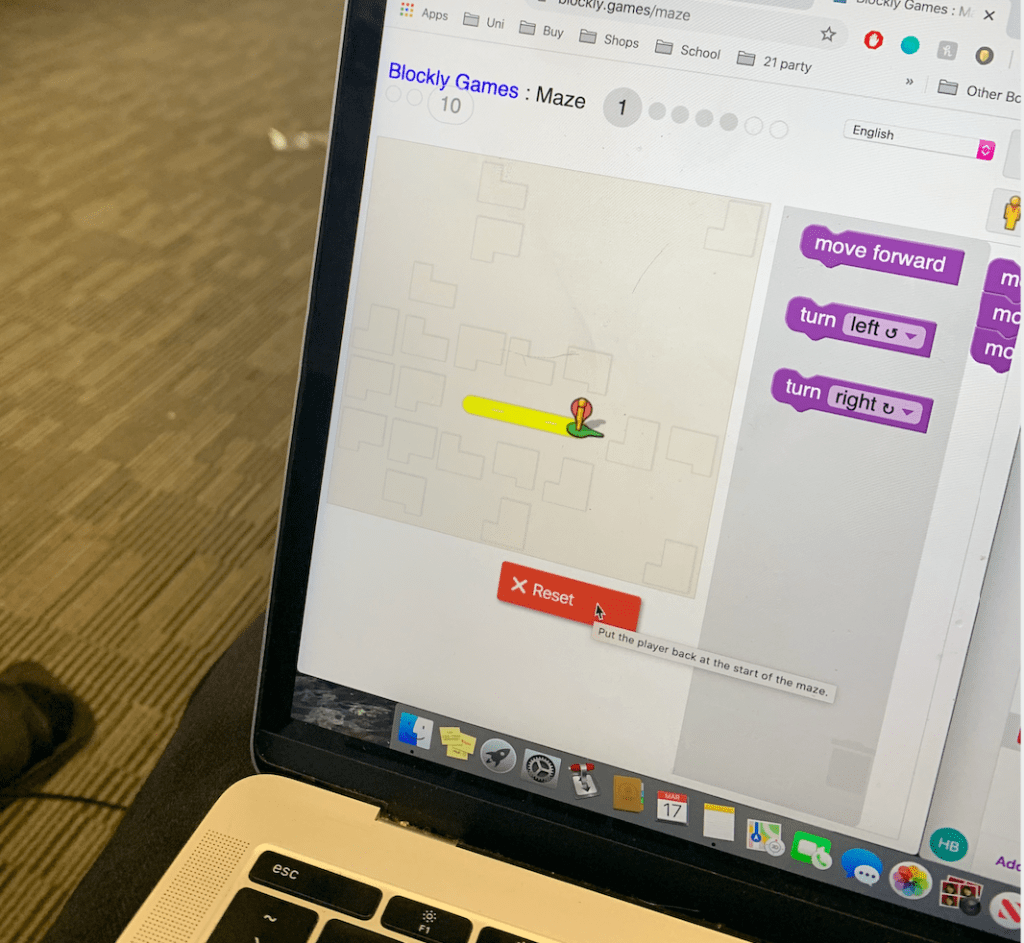

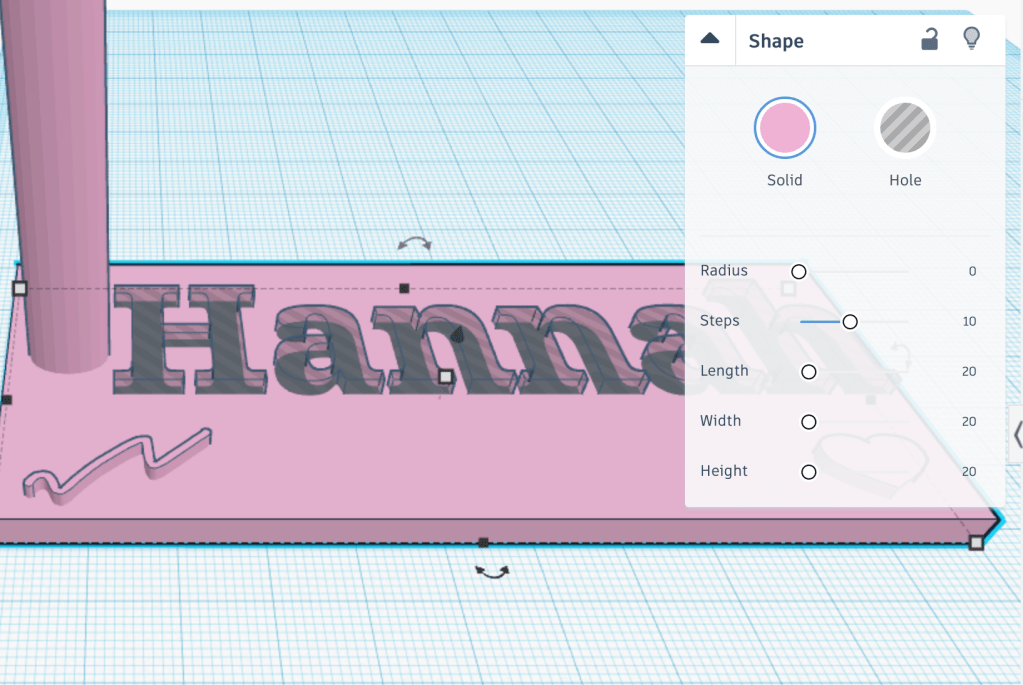

This app may benefit students, mainly in K-3 who are developing fine motor skills or revising/ starting a topic, as it is interactive and can foster student’s willingness to learn, while also nurturing their creativity. As students create their own coloured pages, they develop a sense of pride, leading to higher engagement (Bower, Howe, McCredie, Robinson & Grover, 2014). Lastly, students are able to view and interact with items that would have been difficult to see without the app, e.g. the inside of a volcano, or the components of a cell.

However, a limitation of Quiver is it only works with provided sheets, so students are not given the freedom to express their creativity and design their own detailed sheets. This would have increased their empowerment and higher order thinking, as well as their creativity. It is essential for students learning to involve creativity, thus challenging them to explore their own ideas. Creativity involves exploration, risk taking and experimentation but colouring in pictures doesn’t allow students to partake in this (Bower, et al. 2014). Concurrently, these drawings do not allow for differentiation, which may develop student’s disappointment and an unwillingness to participate (Wu, Lee, Chang & Liang, 2013).

‘Quiver’ could be integrated into the classroom, however, it needs extra learning tools alongside it, such as hands on interactive learning, to become a more creative learning sequence. Whilst ‘Quiver’ is limited in its capabilities and lack of room for creativity, it highlights a great potential for the future of AR in the classroom. AR can greatly benefit the classroom as students are able to interact with materials and concepts that otherwise would not have been possible due to factors such as risk. They are able to explore the world around them in new ways and engage with a large variety of subject matters without leaving the classroom, thus improving their conceptual understanding (Bower, et al., 2014).

References

Billinghurst, M., & Duenser, A. (2012). Augmented Reality in the Classroom. Computer, 45(7), 56-63.

Bower, M., Howe, C., Mccredie, N., Robinson, A., & Grover, D. (2014). Augmented Reality in education – cases, places and potentials. Educational Media International, 51(1), 1-15.

Green, Jody., Green, Tim., and Brown, Abbie. (2017). Augmented Reality in the K-12 Classroom. TechTrends, 61(6), 603-605.

Wu, H., Lee, S., Chang, H., & Liang, J. (2013). Current status, opportunities and challenges of augmented reality in education. Computers & Education, 62(C), 41-49.